Hello! My name is Kate Lochridge, and I am a marine biology and fine art dual major from Bowling Green, Ohio. One of the best parts of science is sharing it with the community. One way to do that is by using fine art to help new audiences access and understand topics they would not otherwise be exposed to.

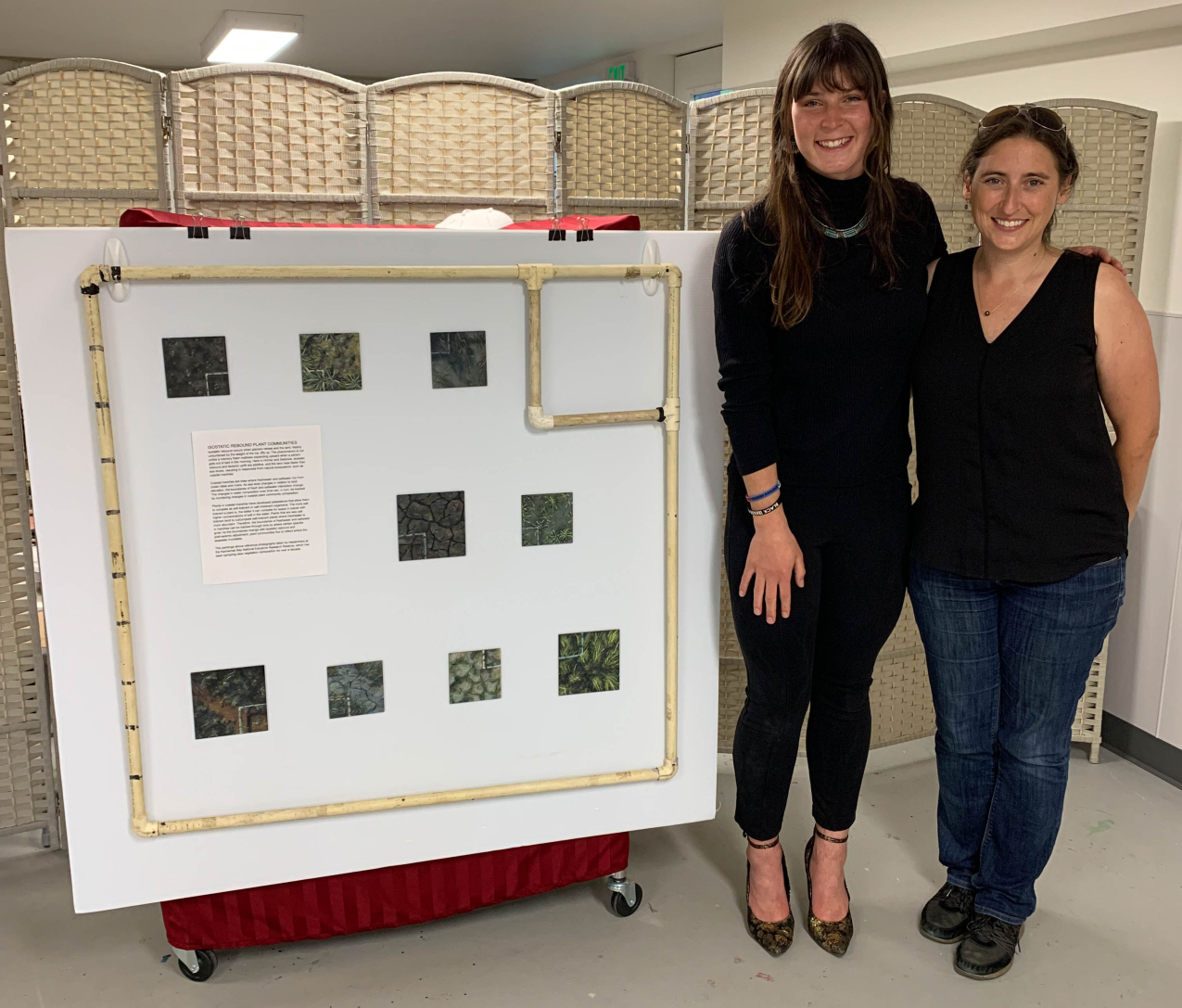

Kate and her mentor, Nicole Kinsman, Ph.D., standing in front of Kate’s “Isostatic rebound” module. (Image credit: Nic Kinsman/National Geodetic Survey)

This is so important to me that the purpose of my internship was to use fine art to translate information from scientific reports, site visits, interviews with scientists and artists, and plein air observations (creating art while directly observing the environment) to encourage public discussion about sea level change in Southcentral Alaska.

My Hollings artist-in-residence experience at Kasitsna Bay Laboratory and with the Kachemak Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve resulted in an exhibit with multiple elements: a sketch journal and four sets of thematically grouped paintings that focused on the process of collecting data, illuminating ecosystem adaptation, the impact of earthquakes on local sea level, and creative education strategies. The collection was displayed at a free two-hour art show that was open to the Homer, Alaska, community, and it was attended by more than 85 people.

Getting to work with Kate ... and the whole network she built during her internship opened my eyes even more to the importance of including the fine arts in science. The discussion I was seeing happening at her final shows were like little sparks in the air - you could almost see them and definitely feel them.

Tour Kate's art show

This panorama shows the setup of Kate's art show. You can view a few paintings from each module of Kate's show below the panorama. The show consisted of four modules, each of which address a topic related to sea level change in southcentral Alaska. From left to right: “Impacts on ecosystems,” “Behind-the-scenes of data collection and production,” “Rapid vertical land movement,” “Novel methods of communication on glacial melt.”

Impacts on ecosystems: Isostatic rebound

In coastal marshes, isostatic rebound can cause shifts in salt water extent and salt water concentration. Isostatic rebound occurs when glaciers retreat and the land, freshly unburdened by the weight of the ice, lifts up. The paintings in this module reference photographs taken by scientists at the Kachemak Bay NERR who research coastal marsh plant communities, which change in response to shifts in the boundary between fresh and salt water.

Behind-the-scenes of data collection and production

In Southcentral Alaska, the land is uplifting faster than the ocean is rising, resulting in decreasing sea levels in the region (relative sea level change), even as the ocean level rises globally. Scientists predict that as the rate of sea level rise accelerates under future climate change scenarios, it will eventually catch up with, and surpass, vertical land movement in Southcentral Alaska. Regional planners need projections of future relative sea level rise to build resiliently, and creating such projections requires scientists to collect large amounts of data. The paintings in this module illuminate the data collection and processing needed to provide sea level rise projections to the public.

See the 2022 sea level rise technical report, which includes the information discussed above.

The paintings in this module were based on source images taken by NOAA contractor JOA Surveys LLC.

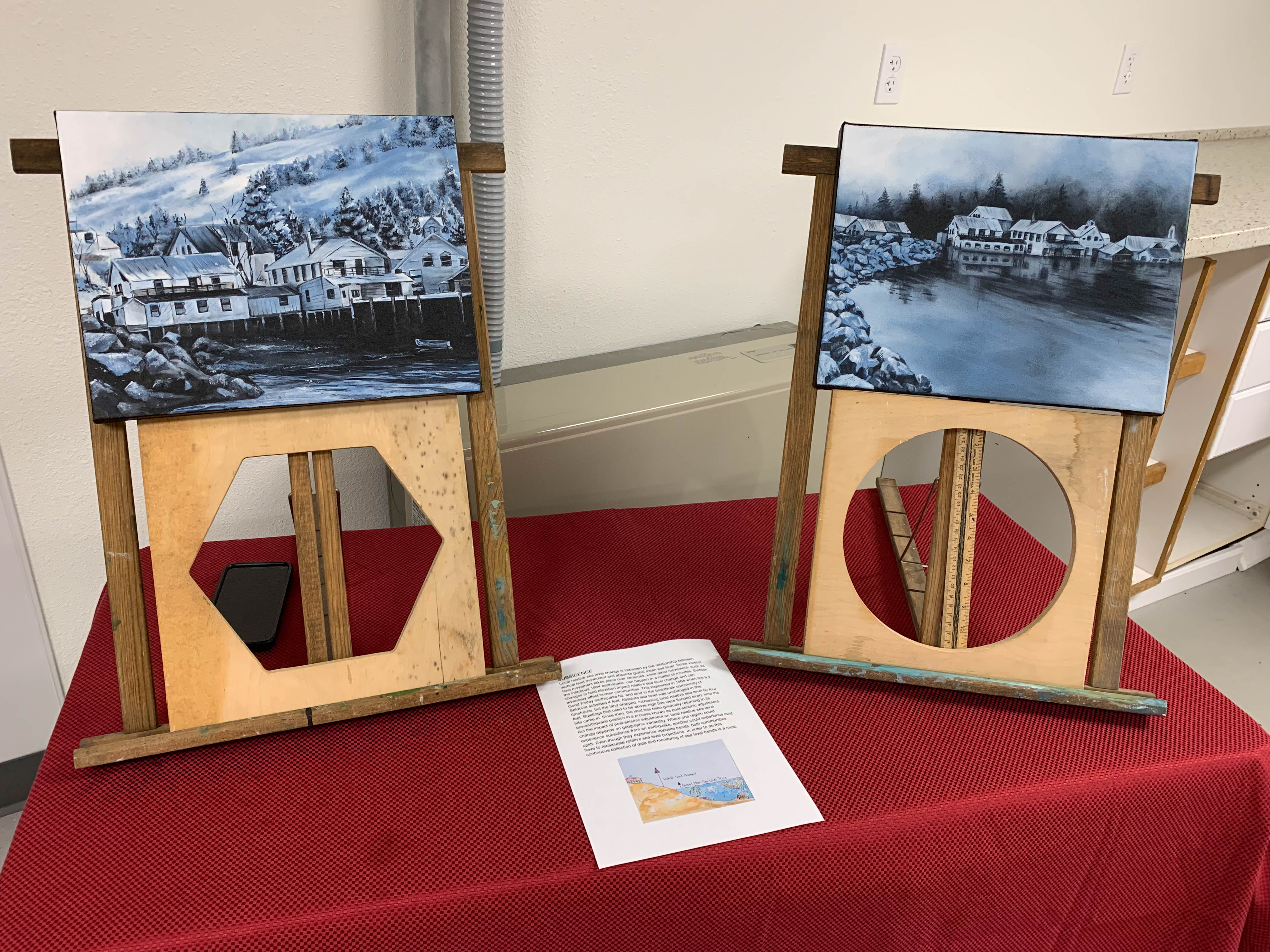

Rapid vertical land movement

Some vertical land movement that affects relative sea level changes takes place over centuries, while other movement caused by seismic events, such as Alaska's infamous 1964 earthquake, can happen in a matter of minutes. Here, Kate shows how sinking of the ground (subsidence) associated with the 1964 earthquake dropped portions of the town of Seldovia, Alaska, below local mean sea level, resulting in coastal flooding and highlighting the highly variable nature of sea level trends in areas that experience rapid vertical land motion.

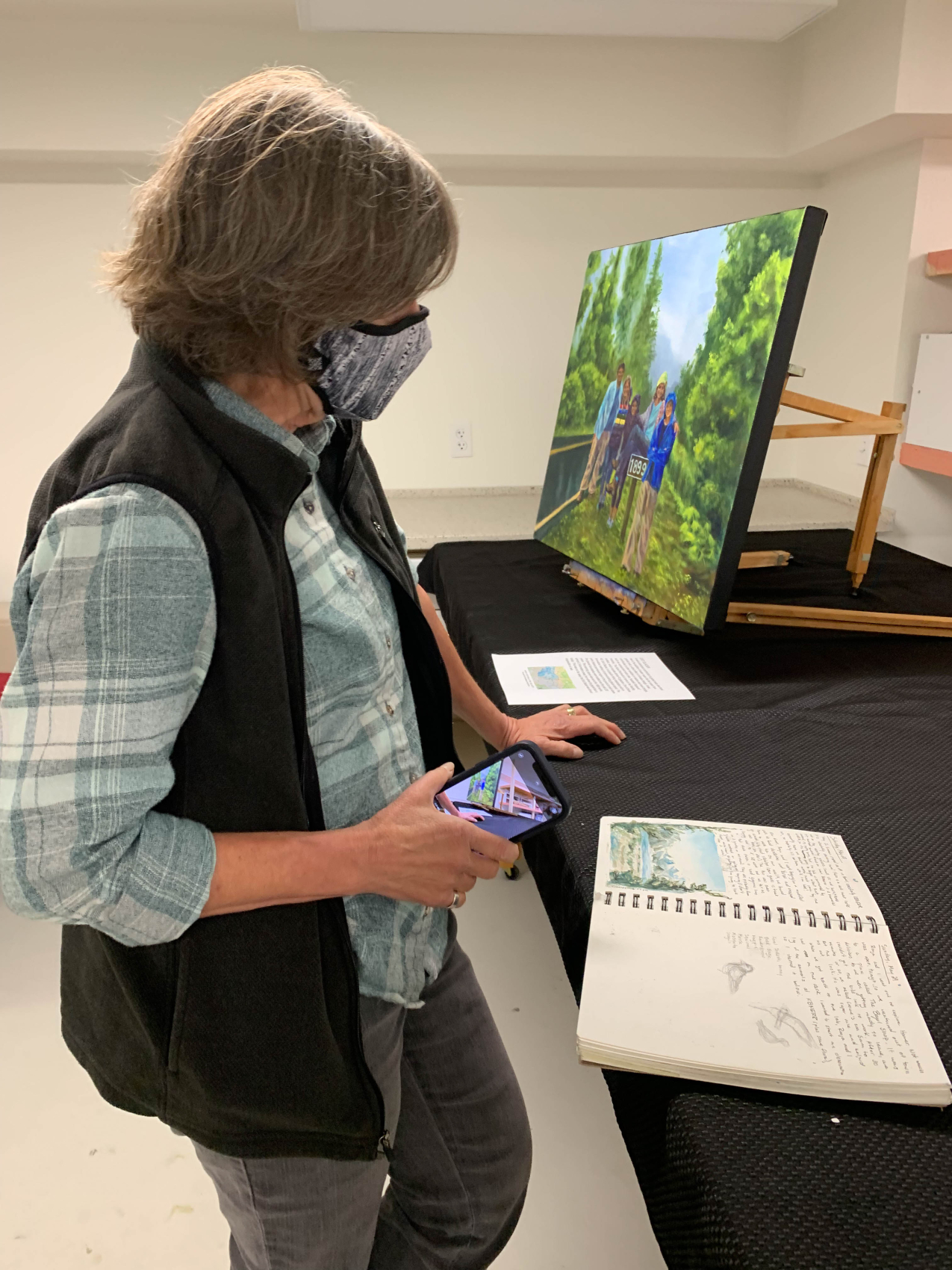

Novel methods of communication on glacial melt

This module featured a painting and Kate's sketchbook. The painting shows fellow Hollings summer interns standing near a marker that showed the extent of the Exit glacier in the year 1899 along a trail where visitors can hike and learn about glacial retreat and ecological responses. While working on her sketchbook, Kate spoke to many people about her work and the scientific processes she saw reflected in the surroundings that she illustrated.

Kate Lochridge is a marine biology and fine art double major at Bowling Green State University offsite link.