Scientists are kind of like detectives answering questions about our natural world. I’m Kate Laboda, a NOAA Hollings Scholar, and I spent my summer internship Nancy-Drewing it at an oyster farm in Juneau, Alaska. I was trying to find out how many males and females were in the farm’s oyster population to aid in developing a local oyster hatchery. We found something very curious … no females!

Building a case file: Background materials

Pacific oysters in Southeast Alaska

Farmed Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas) are unique in Southeast Alaska. These oysters are not native to the region, and year-round water temperatures are too cold for oysters to naturally reproduce. Even though they can’t reproduce, oysters live and grow just fine in these cold waters. In fact, oysters are an important species in Alaska’s growing shellfish aquaculture industry. In order to grow this industry, we need more information about the population dynamics of these oysters.

In Southeast Alaska where oysters do not naturally reproduce, farmers must purchase oyster seed (baby oysters) from out-of-state suppliers. Scientists in Alaska are working on creating an in-state hatchery to potentially reduce farmers’ cost and increase the amount of oysters that can be grown. My research was aimed at understanding sex ratios of Pacific oysters so that we can come up with solutions for promoting oyster reproduction in Alaska.

What is a sex ratio?

Understanding the ratio of males to females, or the sex ratio, of the population is one way we can support future hatchery efforts of farmed Pacific oysters. These sex ratios are important because they can give us clues about a species’ health and future success. In a species such as the Pacific oyster, which mature and reproduce as males first before developing into reproductive females, a sex ratio can also give us clues about how old a population is and what conditions are needed to induce these sex changes.

On the case: My summer project

Gathering evidence

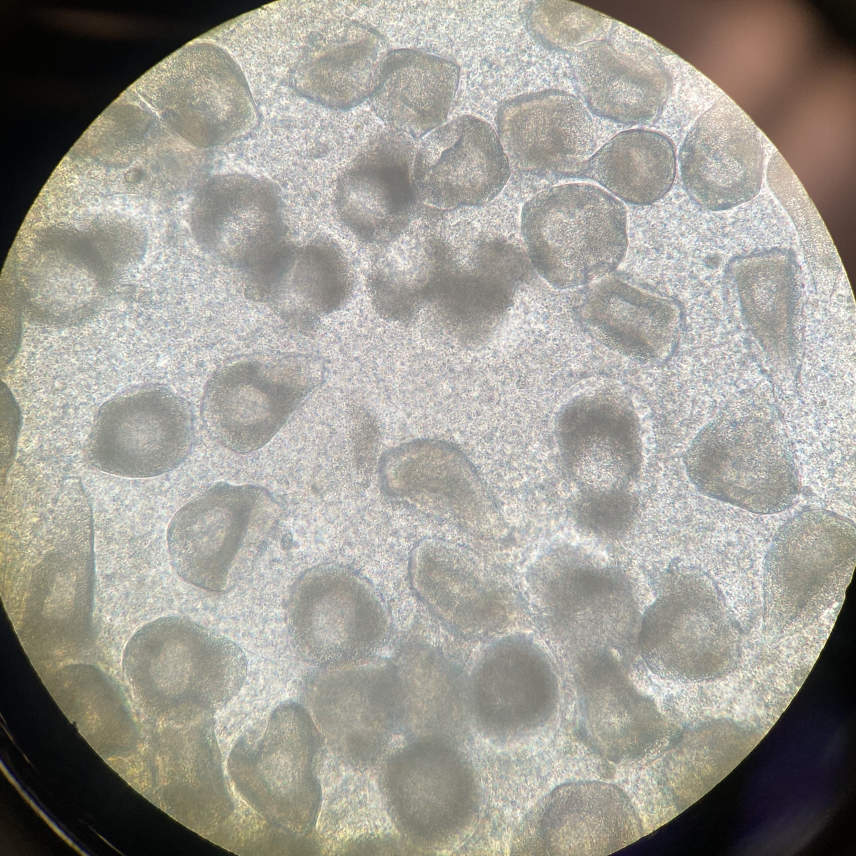

This summer, I collected adult oysters from an oyster farm outside of Juneau, Alaska, once a week for eight weeks. Back in the lab, I dissected a bit of the oyster gonads to look at under the microscope and determine the sex of the oyster. We had some really interesting results! There were a majority of male oysters, but as the summer progressed, we saw more and more oysters with both sperm and eggs present, indicating they were hermaphrodites. But we never saw any female oysters (oysters with eggs, but no sperm)!

Generating new leads

Even this unexpected result is helpful information. We now know that we may not be able to expect female oysters to be present in such a population living in cold water like our farmed oysters. This means we will have to explore more alternatives to supplying an in-state hatchery than simply using any oysters from the region. And now we can start thinking about why we noticed a lack of female oysters. Could it be because the water temperature in Alaska is too cold for oysters to complete their sex change from male to female? Another line of investigation is to look over a longer period of time: My project only examined oyster sex through early August, but if oysters develop later in the season, we might have different findings if we collect them later. Or we could collect oysters earlier in the season and induce sex change and spawning by increasing the water temperatures of the hatchery.

Investigation summary

After spending my summer with the oysters of Alaska, I uncovered some mysteries and found many more. I looked at the sex ratio of Pacific oysters on an oyster farm outside of Juneau in the hopes of developing an in-state hatchery. Our shocking result was the total absence of females — another mystery in itself! But that’s the great thing about being a scientist, there are always exciting mysteries to solve.

Kate is a 2022 Hollings scholar studying biology at Fordham University. Her internship research at the NOAA Fisheries Alaska Fisheries Science Center was on environmental influences on the population sex ratio of farmed Pacific oysters in Southeast Alaska.