Drift bottles were once important scientific tools

Drift bottles have become poetic symbols of loneliness: A desperate person writes an open letter to the world, closes it up into a bottle, and tosses it into the sea in the hopes of making a connection or being found and rescued from their shipwreck on a distant island.

But before the 1970s, many important scientific studies were conducted via bottle.

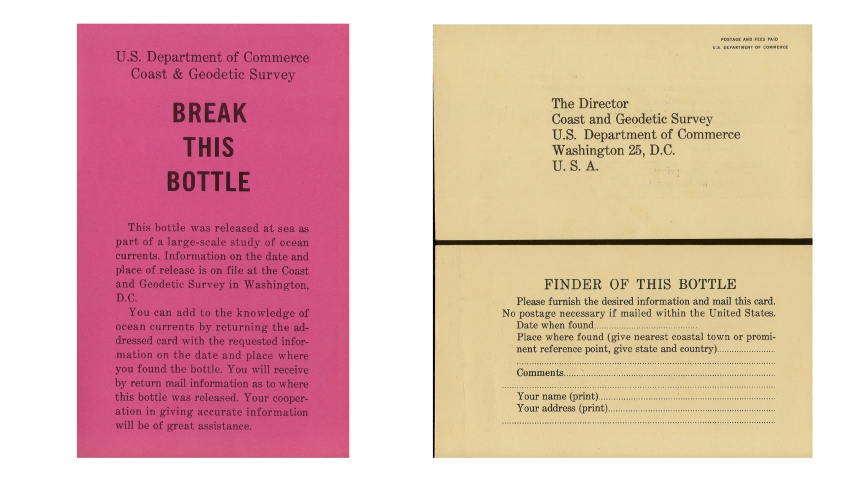

Bottles like this one were used by scientists up until the middle of the twentieth century for studying ocean currents. This one was left unused during a 1959 study conducted by the Coast and Geodetic Survey, a bureau which was later incorporated into NOAA.