A look at some of America’s earliest citizen scientists

Today’s citizen scientists are volunteers who gather data and pass it along to researchers trying to answer big scientific questions. But in the 18th and 19th centuries, many people working to answer those questions were citizen scientists. In fact, some of the most recognizable names in U.S. history collected data in the name of research.

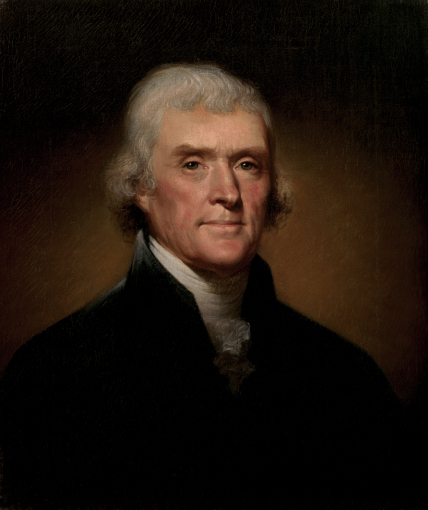

Benjamin Franklin, Benjamin Banneker, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Eunice Newton Foote (Image credit: NOAA Heritage)

1. Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790)

Benjamin Franklin’s most well-known scientific experiment is undoubtedly demonstrating the connection between lighting and electricity with his kite, but did you know that he charted the Gulf Stream to help ship captains navigate it more efficiently? This contributed to our overall understanding of how global trade can be affected by the ocean’s currents.

He also figured out how Nor’easters move. These storms seem to come from the Northeast, but the storm system is actually traveling from the Southwest and interacting with winds from the Northeast, which increases their power. The Great Blizzard of 1888 and the 1993 Storm of the Century are two such storms.

Franklin’s invention of swim fins at the age of 11 earned him an induction into the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 1968.

2. Benjamin Banneker (1731-1806)

Benjamin Banneker was a professional surveyor, as well as a mathematician and astronomer. In 1792, he published an almanac called, “Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia Almanac and Ephemeris.” It included astronomical events like sunrise and sunset, as well as high and low tides. According to the White House Historical Association, as a free Black man living in a slave state, Banneker was frustrated that his scientific work offsite link was never given consideration without mention of the color of his skin and frequently defended its integrity.

3. Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826)

President Thomas Jefferson founded the U.S. Survey of the Coast, a predecessor of NOAA and the nation’s first scientific agency. He promoted scientific exploration and encouraged explorers to study scientific fields, such as botany, land surveying, and astronomy while they were preparing for the journeys.

Jefferson logged daily weather observations in his journal, much like the citizen scientists of today. He tried to collect data on winds and humidity, but the instruments available to him at the time were not capable of those measurements. In his zeal to establish a nationwide climatic record, he directed Meriweather Lewis and William Clark to gather similar daily observations on their momentous exploration of the Louisiana Purchase beginning in 1804.

In 1797, shortly after he became the United States vice president, he was elected president of the American Philosophical Society (which focuses on science) and held the position for nearly two decades.

4. James Madison (1751-1836)

President James Madison also made weather observations in his journal, a practice that was common for the time. He helped with Jefferson’s research by observing the climate and fauna in Virginia. With this information, they were hoping to counter the scientific view at the time that the New World’s humid, cold climate caused there to be fewer species and smaller animals.

Jefferson’s and Madison’s work helped build the nation’s historical climate record, perhaps placing them among some of the nation’s first climate scientists.

5. Eunice Newton Foote (1819-1888)

Eunice Newton Foote was unnoticed in the annals of climate history until recently. She was an amateur scientist—known as a natural philosopher in the 1850s. Foote did some of the first experiments exploring the influence of different atmospheric gases in the “heat of the sun’s rays.” Foote demonstrated that atmospheric water vapor and carbon dioxide can affect solar heating. This presaged John Tyndall’s later experiments describing the workings of the greenhouse effect. Her work in forming foundational standards in this area has often been overlooked in meteorology disciplines.

Foote attended the first woman’s rights convention, the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention. She and her husband Elija signed the convention's Declaration of Sentiments, which first asked for equal social and legal rights for women. She was a friend of suffragist Elizabeth Cady Staton, the main organizer of this historic event.

Did You Know?

Before the first government weather-warning office formed in 1870, weather observation in the United States was performed primarily by volunteers.

Thomas Jefferson first started recruiting volunteer weather observers around Virginia in 1776. By 1800, five other states were involved in the effort. Joseph Henry, first secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, was an early experimenter with telegraphy and had a vision of using data collection for climate studies and forecasting. By 1849, Henry had persuaded telegraph companies to transmit local weather data to the Smithsonian through a network of 150 volunteer weather observers around the country. Before the start of the Civil War, the volunteer network expanded to around 600 people. Shortly after the formation of the first national weather service in 1870, Henry approved the transfer of these observers to the fledgling weather service. By 1891 there were 2,000 weather observation stations spread across the United States..

In 1953, Dr. Helmut Landsberg of the Weather Bureau established a plan to have weather observers spread evenly throughout the nation at intervals of 25 miles.

There are now approximately 10,000 cooperative weather observers in the United States and many other kinds of observers, as well.