Marine animals, including humpback whales, use underwater sound to communicate, navigate, find food and mates, and avoid predators. (Image credit: NOAA National Marine Sanctuary Program)

Soundcheck: Ocean noise

What is ocean noise?

Animals make noise and hear ours too

Waterways getting busier, noisier

Finding solutions

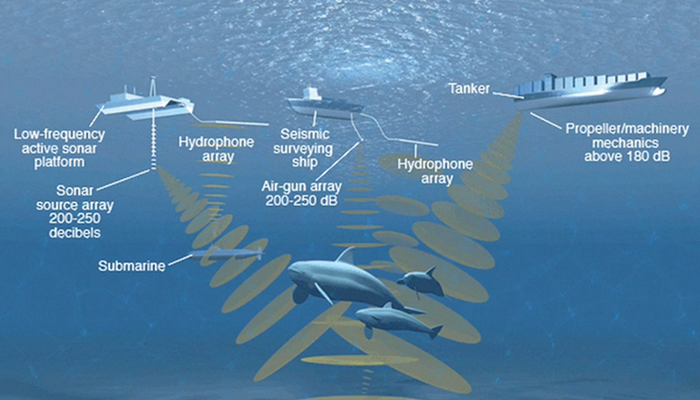

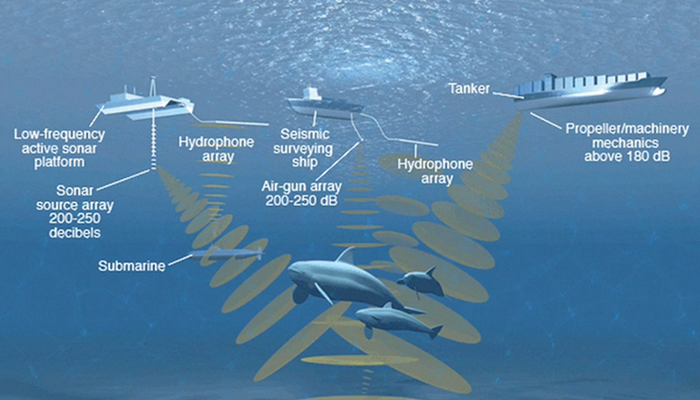

The ocean has always been a noisy place. Many natural sources—like storms, earthquakes, and animals—create underwater sounds. But with the rise of the industrial age, levels of underwater noise from human activities—including from ships, sonar, and drilling—increased dramatically.

Not all sound is created equal. Sources of ocean noise vary in many ways, including how loud they are (intensity, measured in decibels), how long they last (fractions of a second to never ending), and their pitch or tone (frequency, measured in hertz). Think about frequencies relative to tones on a piano. Way down low on the bottom keys are the frequencies that most of the large whale species, as well as large numbers of fish species, use to communicate.

Those growing levels of ocean noise affect marine animals and habitats in complex ways. For one thing, sounds below the surface differ from noises you hear above the waves. Underwater, noises travel farther. In one experiment from the early 1990s, researchers placed a speaker near Antarctica, played some low-frequency or deep-pitched sounds, and picked up those sounds near Bermuda—demonstrating that sound can literally travel halfway around the world.

NOAA has a responsibility to protect marine species and their habitat, which is why we’re working with scientists around the world to further our understanding on ocean noise. Our data and information ultimately help government agencies and industries reduce effects on our ocean resources.

Noise comes in many flavors—ranging from short-term, loud bursts with potentially acute impacts, to long-term, lower level chronic degradation of the background noise environment. NOAA has a role in trying to understand and manage the effects from each.

Marine animals use underwater sound in many important ways. Just as people talk to each other, marine animals use sound to communicate. However, also like people, vocal marine species hear much more than the sounds they use to communicate with one another. Marine species use their hearing to find food and mates, avoid predators, and navigate. Sound is critical to the survival of a great many marine species.

These animals have had 40 to 50 million years or more to evolve in their acoustic environment. But with the advent of the industrial age, people have drastically altered the underwater soundscape over the course of roughly a century. And sometimes how people use the marine environment can affect daily life and functions of marine species.

For this reason, NOAA works with other federal agencies and industries, who are proposing projects that might affect marine species and their habitat—such as oil and gas exploration and drilling, construction, or military training activities—that create loud underwater sounds over specified periods of time. If those sounds could negatively affect marine animals or their habitat, NOAA can require measures and can recommend best practices to reduce negative effects. For example, some measures can avoid noisy activities in specific places when they are important to protected animals or are important to fishery species. Other measures seek to reduce noise exposure for sensitive ecosystems within areas of designated national significance, like National Marine Sanctuaries.

Global forecasts continue to suggest large increases in both the size and number of ships, which predict more noise to come.

Commercial shipping growth has greatly altered the soundscape. In some places, like off Central California, scientists see a strong relationship between growth in large commercial shipping fleets and measurements of lower frequency noise. They are the same frequencies used in the songs of male fin whales and blue whales and by spawning fish such as cod and haddock.

Because shipping traffic is such a major contributor to chronic noise, in 2014 the United States (with NOAA and the U.S. Coast Guard at the helm) led a group within the International Maritime Organization in ratifying voluntary guidelines on ways that ships can reduce noise. NOAA will continue to work with partners, including those within the shipping industry, to incentivize building new and retrofitting existing ships to be quieter.

We’re finding win-win solutions to some of our problems. For example, propellers can create bubbles underwater that burst with a signature sound. In addition to noise, those bubbles are thought to create fuel inefficiency. One question is whether a quieter propeller that produces less noise would also be more efficient to make up the difference in upfront cost. Because large shipping companies face pressure to comply with stricter carbon emission standards, propeller changes in tomorrow’s ships could help both shipping operators and the environment.

The United States is not alone in these efforts. Ports in British Columbia, Canada, are creating incentives for shipping companies to figure out how much noise they make compared to other ships and reward those with good environmental status.

NOAA is working with partners around the world to develop new tools to better understand the complexities of ocean noise and is developing strategies that help governments and industries address it.

Given NOAA’s mission to keep marine resources sustainable and resilient for future generations, we recognized the need to tackle the issue of man-made ocean noise in a holistic way. In 2010, NOAA committed to improve tools that the agency uses to assess the effects of man-made sound on whales, dolphins, and porpoises.

12

Current number of underwater reference stations in U.S. waters tracking ocean noise levels over time for the federal government.

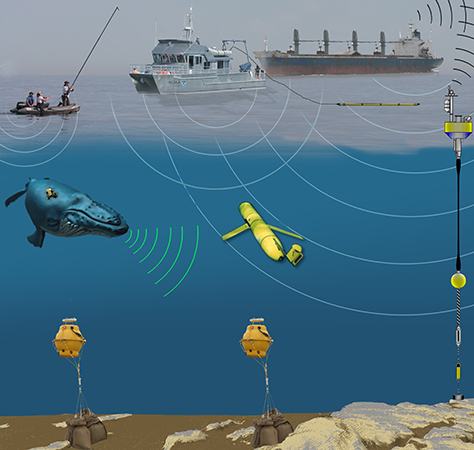

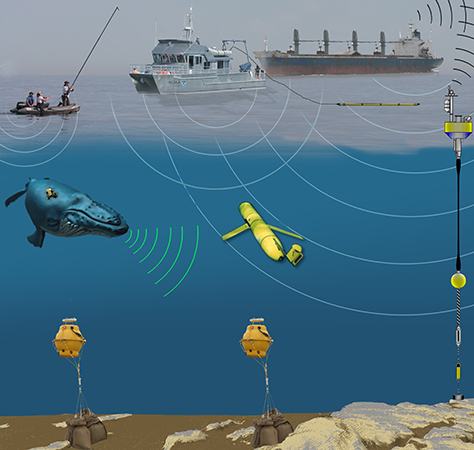

This led to two complementary efforts—one to produce maps of where these animals are located and in what densities within U.S. waters, and another to predict levels of underwater noise from human activities. Scientists can use these maps, along with other information, to better understand what is happening underwater and where higher levels of human-produced noise overlap with the marine mammals. With these maps complete, NOAA began to push forward on a long-term visionary plan regarding ocean noise effects.

In the fall of 2016, NOAA released our final Ocean Noise Strategy Roadmap. The strategy is a NOAA initiative that seeks to guide the agency toward more comprehensive and effective management of the effects of man-made ocean noise over the next decade. The Strategy includes steps to improve what we know about underwater noise, and how we can work to minimize adverse effects of ocean noise on marine species and habitats.

One basic thing we still need to learn more about is how noisy it is in different ocean soundscapes and how those levels are changing through time. This research is ongoing. In the meantime, we’re working with partners on new and innovative techniques to further reduce risk while noisy activities are happening, such as placing observers in the area to stop activities when marine mammals come within a certain distance. And in some cases, measures can be taken to make the activity itself quieter, through the application of quieting designs. Examples include using bubble curtains around a pile or using alternative quieter technologies instead of airguns.

The ocean has always been a noisy place. Many natural sources—like storms, earthquakes, and animals—create underwater sounds. But with the rise of the industrial age, levels of underwater noise from human activities—including from ships, sonar, and drilling—increased dramatically.

Not all sound is created equal. Sources of ocean noise vary in many ways, including how loud they are (intensity, measured in decibels), how long they last (fractions of a second to never ending), and their pitch or tone (frequency, measured in hertz). Think about frequencies relative to tones on a piano. Way down low on the bottom keys are the frequencies that most of the large whale species, as well as large numbers of fish species, use to communicate.

Those growing levels of ocean noise affect marine animals and habitats in complex ways. For one thing, sounds below the surface differ from noises you hear above the waves. Underwater, noises travel farther. In one experiment from the early 1990s, researchers placed a speaker near Antarctica, played some low-frequency or deep-pitched sounds, and picked up those sounds near Bermuda—demonstrating that sound can literally travel halfway around the world.

NOAA has a responsibility to protect marine species and their habitat, which is why we’re working with scientists around the world to further our understanding on ocean noise. Our data and information ultimately help government agencies and industries reduce effects on our ocean resources.

Noise comes in many flavors—ranging from short-term, loud bursts with potentially acute impacts, to long-term, lower level chronic degradation of the background noise environment. NOAA has a role in trying to understand and manage the effects from each.

Marine animals use underwater sound in many important ways. Just as people talk to each other, marine animals use sound to communicate. However, also like people, vocal marine species hear much more than the sounds they use to communicate with one another. Marine species use their hearing to find food and mates, avoid predators, and navigate. Sound is critical to the survival of a great many marine species.

These animals have had 40 to 50 million years or more to evolve in their acoustic environment. But with the advent of the industrial age, people have drastically altered the underwater soundscape over the course of roughly a century. And sometimes how people use the marine environment can affect daily life and functions of marine species.

For this reason, NOAA works with other federal agencies and industries, who are proposing projects that might affect marine species and their habitat—such as oil and gas exploration and drilling, construction, or military training activities—that create loud underwater sounds over specified periods of time. If those sounds could negatively affect marine animals or their habitat, NOAA can require measures and can recommend best practices to reduce negative effects. For example, some measures can avoid noisy activities in specific places when they are important to protected animals or are important to fishery species. Other measures seek to reduce noise exposure for sensitive ecosystems within areas of designated national significance, like National Marine Sanctuaries.

Global forecasts continue to suggest large increases in both the size and number of ships, which predict more noise to come.

Commercial shipping growth has greatly altered the soundscape. In some places, like off Central California, scientists see a strong relationship between growth in large commercial shipping fleets and measurements of lower frequency noise. They are the same frequencies used in the songs of male fin whales and blue whales and by spawning fish such as cod and haddock.

Because shipping traffic is such a major contributor to chronic noise, in 2014 the United States (with NOAA and the U.S. Coast Guard at the helm) led a group within the International Maritime Organization in ratifying voluntary guidelines on ways that ships can reduce noise. NOAA will continue to work with partners, including those within the shipping industry, to incentivize building new and retrofitting existing ships to be quieter.

We’re finding win-win solutions to some of our problems. For example, propellers can create bubbles underwater that burst with a signature sound. In addition to noise, those bubbles are thought to create fuel inefficiency. One question is whether a quieter propeller that produces less noise would also be more efficient to make up the difference in upfront cost. Because large shipping companies face pressure to comply with stricter carbon emission standards, propeller changes in tomorrow’s ships could help both shipping operators and the environment.

The United States is not alone in these efforts. Ports in British Columbia, Canada, are creating incentives for shipping companies to figure out how much noise they make compared to other ships and reward those with good environmental status.

NOAA is working with partners around the world to develop new tools to better understand the complexities of ocean noise and is developing strategies that help governments and industries address it.

Given NOAA’s mission to keep marine resources sustainable and resilient for future generations, we recognized the need to tackle the issue of man-made ocean noise in a holistic way. In 2010, NOAA committed to improve tools that the agency uses to assess the effects of man-made sound on whales, dolphins, and porpoises.

12

Current number of underwater reference stations in U.S. waters tracking ocean noise levels over time for the federal government.

This led to two complementary efforts—one to produce maps of where these animals are located and in what densities within U.S. waters, and another to predict levels of underwater noise from human activities. Scientists can use these maps, along with other information, to better understand what is happening underwater and where higher levels of human-produced noise overlap with the marine mammals. With these maps complete, NOAA began to push forward on a long-term visionary plan regarding ocean noise effects.

In the fall of 2016, NOAA released our final Ocean Noise Strategy Roadmap. The strategy is a NOAA initiative that seeks to guide the agency toward more comprehensive and effective management of the effects of man-made ocean noise over the next decade. The Strategy includes steps to improve what we know about underwater noise, and how we can work to minimize adverse effects of ocean noise on marine species and habitats.

One basic thing we still need to learn more about is how noisy it is in different ocean soundscapes and how those levels are changing through time. This research is ongoing. In the meantime, we’re working with partners on new and innovative techniques to further reduce risk while noisy activities are happening, such as placing observers in the area to stop activities when marine mammals come within a certain distance. And in some cases, measures can be taken to make the activity itself quieter, through the application of quieting designs. Examples include using bubble curtains around a pile or using alternative quieter technologies instead of airguns.