April 2023: Science First Responder and Incident Meteorologist (IMET) Robert Rickey takes a helicopter flight to observe terrain and fire activity in California. Sometimes fires burn in locations so remote, the best vantage point to assess the fire is from above. (Image credit: NOAA)

When a large wildfire breaks out, NOAA’s National Weather Service (NWS) is on the scene to help fight fires with weather forecasts.

Specially trained Science First Responders, commonly known as Incident Meteorologists, or IMETs, deploy to a wildfire to serve as key members of wildfire incident command teams. These specialty forecasters provide critical information that wildfire managers and first responders need to successfully and safely contain fires. IMETs also support operations at prescribed fires by providing site-specific spot weather forecasts to help with tactical decision-making.

NWS employs more than 100 IMETs, including fully qualified professionals and trainees, located in NWS offices across the country. As soon as a large wildfire breaks out, the incident commander can submit a request to NOAA to deploy an IMET to their site. Typically an IMET arrives at the incident within 24 hours.

We talked with IMET Rickey to find out how he prepares for deployment, and what his day looks like when working a major wildfire. Rickey joined the IMET program in 2017, and in 2023 he was deployed for 73 days. When not deployed, he serves as the Science and Operations Officer at the NWS Weather Forecast Office in Flagstaff, Arizona.

How do you prepare for a wildfire deployment?

I have to be ready at a moment’s notice. I keep my bags packed and gear in good working order so that when I do get the call, I can spend my time learning the history of the fire, its current status and the weather.

Describe what happens at an Incident Command Post.

It can feel like a small town at the Incident Command Post (ICP). Depending on the size of the fire, there might be hundreds of people working.

The ICP operates numerous sections, including finance, operations and logistics and they typically supply food, portable shower trailers and portable restrooms. Since many fires occur in remote locations, hotels aren’t an option. I usually sleep in a tent or bring a blow-up mattress and sleep in the back of my vehicle.

I get an overwhelming sense of job satisfaction because I know that what I am doing is important. My real-time weather information provides fire crews and the general public with alerts and warnings they need to stay safe.

What does a typical day in the field look like for an IMET?

Days are long … usually 16 hours. Much of my day is spent making specialized weather forecasts for the area and briefing decision-makers about the forecasts. Most days begin with a 6 a.m. operational briefing, when I brief fire crews on the weather forecast. I may also brief the helicopter pilots who are fighting the fire by air, and stakeholders who are impacted by the fire, such as ranchers and utility companies. When time allows, I take a trip to the fire line to examine the terrain and consult with firefighters to refine my forecasts based on their decision support needs.

If thunderstorms are a possibility, I closely monitor radar so that I can broadcast radio alerts to crews to warn them of approaching storms. Thunderstorms are particularly hazardous to firefighting crews on the frontline, because they can produce lightning, gusty outflow winds and flash flooding. The safety of the crews working the fire is paramount. When storms are in the area, they must pull back to a safe location.

When I’m not delivering a weather briefing, I am producing the forecast, gathering observations and sometimes giving interviews to reporters.

How long does an IMET deployment last?

The length of an IMET deployment varies anywhere from a couple of days to two weeks, depending on the state of the fire and containment. If a fire lasts more than two weeks, typically a new IMET will relieve the existing IMET.

Is forecasting for wildfires different from general weather forecasting?

IMETs make forecasts that are specifically tailored to the area where a fire is located, with an emphasis on the weather elements that drive fire activity such as wind speed and direction.

Forecasting for wildfires is exceptionally challenging because of scale. The general weather forecast broadly describes the weather, whereas a fire weather forecast may aim to predict the wind and humidity within a particular valley, along a mountain slope or over a ridgetop.

Large fires can, to a degree, create their own weather. For example, under the right conditions, a vigorously burning fire can produce a smoke column that develops into a storm capable of producing lightning and erratic winds.

Tell us about prescribed burning assignments. Why are they important?

Most of my assignments last year were for prescribed burning on the Kaibab National Forest in Arizona. Prescribed burning, or “beneficial fire,” is when firefighters intentionally burn a piece of land to reduce the potential for larger, more destructive wildfires in the future.

National forests are increasingly requesting IMETs to support their activities during prescribed burns. The spot forecasts I provide help determine the best time to conduct a burn since firefighters need safe weather conditions before they start a prescribed burn. Once the prescribed fire begins, I remain in the field to support the effort by taking weather observations, gathering intel and issuing alerts for any hazardous or unexpected weather conditions.

What is an IMET’s biggest challenge?

Time management is critical, especially when the fire is raging. With many responsibilities, 16-hour days seem long, but sometimes that’s not even enough.

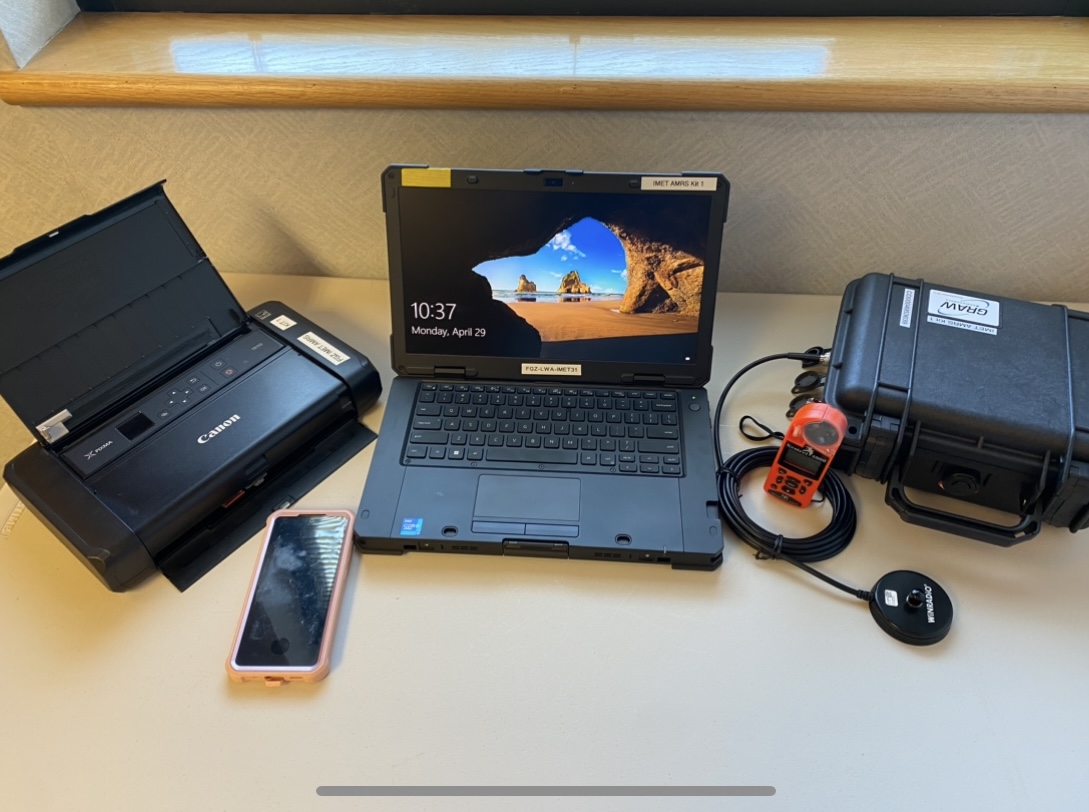

Plus, IMETs need a lot of data and good Internet access to do our jobs well. We need to see weather models, observations, satellite imagery and radar data to develop a forecast, and reliable internet access is key. There have been times when I’ve literally driven miles to the next closest community to find a business with publicly available internet to get my job done.

What do you like most about being an IMET?

I get an overwhelming sense of job satisfaction because I know that what I am doing is important. My real-time weather information provides fire crews and the general public with alerts and warnings they need to stay safe. In addition, my weather forecasts are used to design strategies to contain the fire.