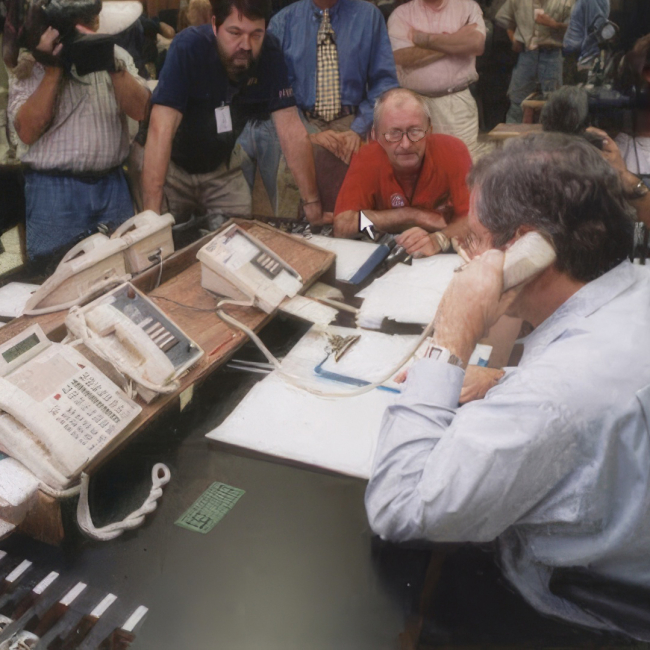

These Hurricane Hotline phones sit in all of their old beige glory, on display in the lobby of the Weather Forecast Center in College Park, Maryland.

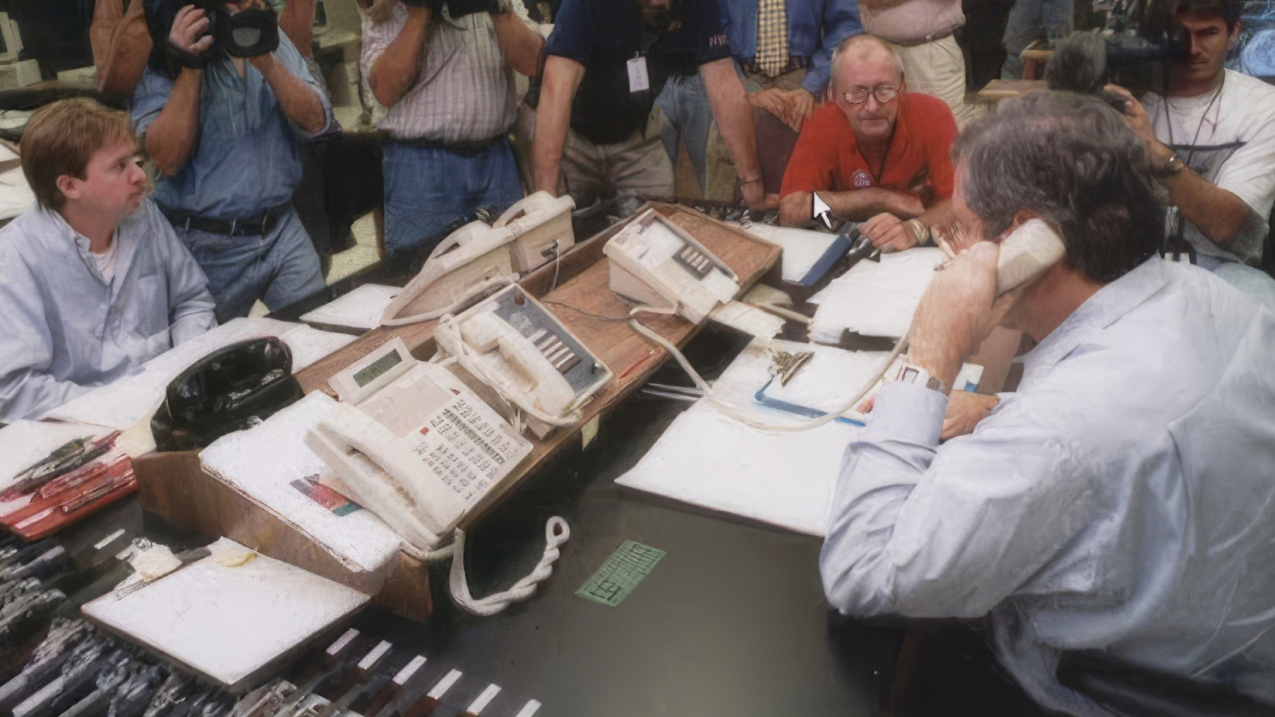

This colorful photo shows reporters filming Hurricane Specialist Richard Pasch making a hurricane conference call with the National Weather Service New Orleans/Baton Rouge Office during Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Digitally enhanced photo. (Image credit: NOAA)

If you could pick up the receiver on one and hear all the conversations that ever took place through their wires, you’d hear stories of horrible winds, torrential rains, flooding, high tides, near misses, and the voices of forecasters using every possible tool they had to anticipate the path of coming storms. You’d also hear the important collaborative work of National Weather Service experts preparing to explain storms to the public.

These devices were never used to talk to the general public, however. Instead, the Hurricane Hotline was plugged into a dedicated landline phone system in the late twentieth century that enabled experts from different states and regions of the U.S. to talk directly with each other quickly. Forecasters could connect one-on-one or use the line to host a conference call. In a time before shared screens and online meetings, they enabled experts to assess data about storms and share the latest important information with each other without having to wait through a crowded switchboard or a busy signal.

All during the hurricane season (June to November), someone was assigned to monitor them from their desk in the weather forecast offices. A ring on one of these meant someone in the NWS chain of command wanted to share sensitive and important information quickly and without interruption. If a large storm started to brew in the Western Atlantic, these phones were likely to ring.

The red bulb on top lit up when a call was coming in, enabling office workers to see what couldn’t be heard over the clack-a-clack of noisy typewriters, the ringing of dozens of other phone lines, and the voices of people working across desks in the bullpen-style office suite. Many offices were a lot noisier before computers took over, cubicles were built, and interoffice texting and chatting silenced the general cacophony of getting things done. Forecast offices, especially.

“When a tropical cyclone was in progress a hotline call would be scheduled for a certain time, usually every six hours,” says Richard Pasch, a senior hurricane specialist who has worked at the National Hurricane Center since 1989. “I remember them being used for storms like Hurricane Andrew, in 1992 and many others, too. There was static on the line sometimes, but it was still an advantage to have a phone linked like that so we could coordinate our watches and warnings before advisories became official.”

The lines were also used for calls with the Navy, the Coast Guard and the Department of Defense during storm preparation, Pasch says.

Records are not available for when these phones were decommissioned, although Pasch remembers them being in place all the way into the early 2000s.

Calls are still made today between forecasters and other stakeholders, but take place via the internet. There are no landlines connecting offices anymore.