Words like “eerie,” “ghostly” and “haunting” may come to mind when you think of shipwrecks. In addition to these spooky qualities, shipwrecks can also have a big impact on ocean science. Here are six ways how.

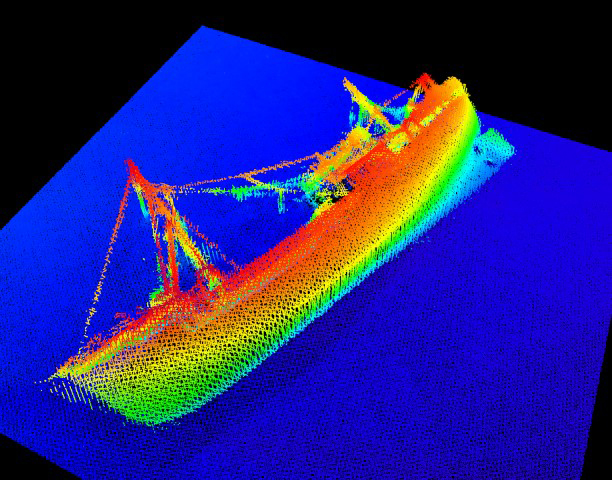

Within Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary lie the remains of nearly 100 shipwrecks that represent a microcosm of maritime commerce and travel on the Great Lakes. The D.M. Wilson, a wooden bulk freighter, sank in 1894 after springing a leak. Most of the Wilson's hull remains intact today in the sanctuary, including a large windlass that rests on the bow. (Image credit: NOAA)

1. Shipwrecks can serve as “underwater skyscrapers.”

Ecologists studying the areas around shipwrecks have recorded high fish abundance offsite link. One reason, says NOAA scientist Avery Paxton, may be the way that tall structures jutting up from the sandy ocean floor create a variety of spaces for fish to hide, hunt and rest.

“Shipwrecks are tiny islands of structured habitat,” says Paxton, who works for NOAA's National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science. “They are small but they can support a tremendous amount of marine life. And it seems that the taller the structure, the higher the amount of fish. The wrecks almost become underwater skyscrapers full of ocean residents.”

2. Shipwrecks often occur in large lakes.

Large lakes can provide great shipping channels and connect productive farmland to busy ports. But dramatic storms often form over lakes, just as they do on the ocean, causing sailing there to be challenging and sometimes perilous. NOAA’s Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast National Marine Sanctuary protects 36 known shipwrecks and 59 suspected shipwrecks within its boundaries. Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary in Lake Huron is home to nearly 100 known shipwrecks.

3. There may be as many as 10,000 shipwrecks in North America.

NOAA’s Office of Coast Survey (OCS) uses high-tech surveying methods to reveal long-hidden topographical details and the locations of approximately 10,000 wrecked vessels within our nation’s waterways.

OCS’s work dates back to 1807, when President Thomas Jefferson signed “an Act to provide for surveying the coasts of the United States," and surveyor Ferdinand R. Hassler was hired to lead the scientific work.

Hassler’s survey efforts were sidelined by the War of 1812 but finally began in earnest when he initiated a survey of New York Harbor in 1817. Disagreements soon erupted over whether the work should be under military or civilian control. The civilian U.S. Coast Survey was eventually established with Hassler as superintendent in 1832, and continues to this day as new instruments are used by modern scientists to generate detail-rich maps of underwater areas.

4. A shipwreck can linger for more than a century.

The iconic Civil War ironclad USS Monitor was built to withstand intense naval battles when it was launched in 1862 to fight for the Union Navy. But the design — advanced for its time — was still not enough to help the vessel withstand treacherous winter storms off the coast of North Carolina on New Year's Eve that same year. The resulting shipwreck has been intensely researched since it was rediscovered in 1973. In 2002, when the Monitor’s turret was recovered in a joint U.S. Navy and NOAA mission, it still held the skeletal remains of two of the 16 men who lost their lives on the vessel 140 years before.

5. Shipwrecks are sometimes draped with "ghost nets.”

Shipwrecks can snag the nets of passing fishing boats. Many times, these “ghost nets” help to discover long-lost wrecks.

In 1994, for example, the fishing vessel Mistake threw down a trawling net in the Gulf of Mexico and became ensnared on the Spanish warship El Cazador. The warship sank in 1783 full of silver coins, and its final resting spot was a mystery. That is, until crewmembers aboard Mistake pulled up shiny metal bits and rocks in their tangled netting. The recovered treasure included a large topaz stone and approximately 37,500 pounds of silver. However, experts did not consider the “treasure” particularly valuable.

While fishing nets typically snag debris and rubbish, they have also caught on a wide variety of more valuable items along the Pacific seafloor. Of note: fishing nets helped discover European sailing ships full of gold that was mined during the famous gold rush era of the 1840s.

6. Shipwrecks can be dangerous even decades after they sink.

Shipwrecks are abandoned vessels, and therefore are considered a very problematic type of marine debris. Even decades after a ship sinks, new dangers can arise as tanks holding supplies and fuel degrade and leak.

“Ships are a bit like floating hardware stores,” says Doug Helton of NOAA’s Office of Response and Restoration. “They carry everything a crew would need for daily life and vessel maintenance over many weeks or even months.”

When the Tank Barge Argo sank in Lake Erie in 1937, for example, it was carrying approximately 100,000 gallons of crude oil and 100,000 gallons of benzol. When the wreck was discovered in 2015, it turned into a large and complicated remediation project. Divers investigating the site found a leak of chemicals so powerful they corroded their dive suits and masks. For this reason, underwater explorers — both professional and amateur — are advised to steer clear of wrecks unless a site has been investigated, secured and approved for recreational diving. All visitors should also familiarize themselves with state and federal laws pertaining to shipwrecks before approaching a site.