Six years after Kate Bemis walked into the NOAA National Systematics Lab for the first day of her Hollings summer internship, she returned to the office — only now she was starting the first day of her new career and adding a new label to the door that read "Katherine Bemis, Ph.D.”

Kate Bemis and Bruce Collette in 2016 after they submitted their book, which Kate worked on during her Hollings summer internship, for peer review. (Image credit: Sheila Bell)

From the time she was awarded a Hollings Scholarship in 2013, Kate Bemis was determined to spend her NOAA internship working with Bruce Collette offsite link, a scientist at the NOAA National Systematics Laboratory. Bruce is one of the most well-respected NOAA scientists in the field of ichthyology (the study of fishes), and Kate was eager to learn from him. Usually, Hollings scholars select potential internship projects from a list of opportunities submitted by NOAA offices. But, when Kate saw that Bruce hadn’t listed an internship, she reached out to see if Bruce would be willing to host a Hollings scholar. To her delight, he agreed.

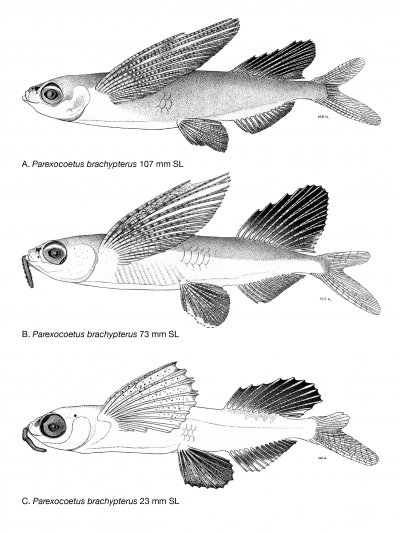

Kate started her internship ready to take on the world, and her enthusiasm was well met — on day one, Bruce entrusted her with 60 years of data and a 450 page manuscript on Beloniformes, an order of fish that includes needlefishes, flyingfishes, and others. She was tasked with preparing the information for publication as an authoritative guide to Beloniformes. “It was super daunting,” said Kate, “but Bruce was a fantastic mentor and gave me complete control, but also worked with me one-on-one to show me how to organize taxonomic information.” Despite the seemingly bottomless amount of information, Kate started paving a path forward by assembling and consistently formatting the materials. Before she knew it, she had enough understanding of the information to edit and write new content for the publication.

By working on this project alongside her mentor, Kate developed a set of skills that she credits with helping her get even more opportunities. “Hollings made me a more competitive applicant,” said Kate. “Writing, data management, figure preparation … were all skills that I talked about when I interviewed for other opportunities and I think that those were really beneficial to me.” Kate and Bruce also worked with Ilia Shakhovskoy, an ichthyologist based in Moscow, which Kate says was a good introduction to international science and collaboration.

After her internship, Kate continued working on the publication with Bruce while she was a Ph.D. student at Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary. The book was finally published in 2019 – 60 years after Bruce started working on it and five after Kate joined the effort – as a monograph in “Fishes of the Western North Atlantic offsite link”1.

Bruce retired from the NOAA National Systematics Lab and his former position opened up. Kate applied and got the position offsite link. “[Being in the same role Bruce had] is kind of mind blowing … it’s basically the best job, I get to study fishes every day!”

Her job is different from what most people picture a scientist doing. “My office is in the Smithsonian, so I’m surrounded by museum collections and people who think about collections and how to use them, but I work for NOAA so my broader goals are framed in the NOAA context,” says Kate, “It’s very special to have access to the communities and resources both NOAA and Smithsonian have to offer.”

Though Kate used to think that succeeding meant working as a faculty member at a university, she is glad that her Hollings internship changed her perspective. In fact, the best piece of advice she offers to other Hollings alumni and recent graduates is to “be open to all opportunities and to where your career is going to take you.” As for current or future Hollings scholars, her advice is similar, “use this time to do anything you want to do. Go to any NOAA lab in the country. It is worth investing time in which mentor you want to work with and which place you want to go.” And for scholars who are interested in ichthyology and fish systematics? Kate says, “Give me a call!”

Are you interested in applying to the Hollings Scholarship? Learn more about the scholarship in the 2021 scholarship application announcement and see the Hollings Scholarship website to apply!

1Collette, B. B., K. E. Bemis, N. V. Parin, and I. B. Shakhovskoy. Fishes of the Western North Atlantic, Part 10: Beloniformes. Eds. B. B. Collette and T. J. Near. Yale University Press, pp. 1-252.