Imagine this: You’re a NOAA scientist working in the remote Arctic, responding to an oil spill, when a storm comes through. One of your fellow scientists falls on the frozen tundra and injures her leg, and — to make matters worse — you see a bear steadily approaching in the distance. What’s your plan?

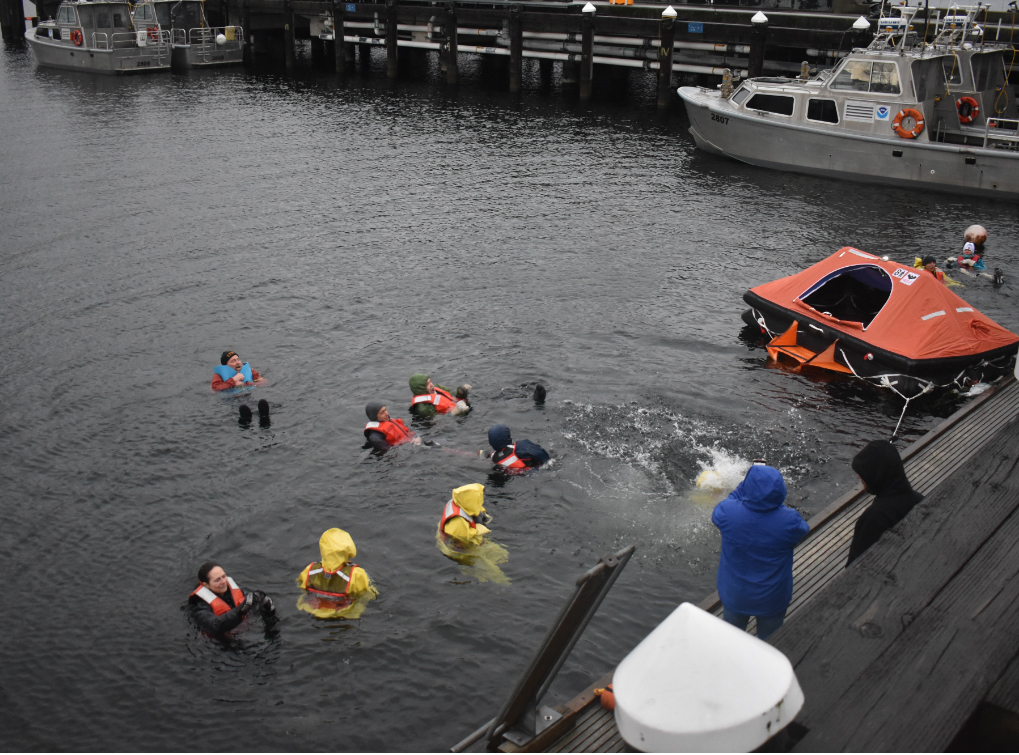

A NOAA scientist practices Arctic survival skills in cold waters of Seattle's Lake Washington, December 2019. Exercises like these teach trainees to focus on survival and the future. Trainees practiced cold-water survival swimming techniques and how to get onto a life raft. (Image credit: NOAA)

Answers to that question are more is the purpose of Arctic Survival Training held in December at NOAA’s Western Regional Campus in Seattle. Attendees practiced emergency first aid, deployed emergency flares, and were chased by a grizzly – an instructor in a bear suit, thankfully – to hone their predator defense and wilderness survival skills.

For four days, NOAA staff learned to “manage the unexpected.” Specifically:

-

Finding adequate shelter;

-

Conserving energy and warmth;

-

Focusing on the task at hand (one thing at a time!); and

-

Most important, how to handle stressful situations well.

In one real-world scenario, participants jumped into 48-degree waters of Lake Washington wearing their street clothes and a floatation device in order to mimic an accident one might need to survive in the Arctic.

“That was the thing we dreaded the most,” said Savannah Turner, a health and safety officer for the NOAA Ocean Service’s Office of Response and Restoration, which responds to oil, chemical and hazardous waste spills often in challenging situations.

“Even though we were only in the water for four minutes, it was painful but worth it. You quickly learn to float by yourself, even though your instinct is to reach out to others. Your reaction is part physical, but also mental and emotional, and the training helps to prepare you for that part as well. You learn to relax, and to focus on comfort and hope in order to survive.”

It’s critical to be prepared for cold water exposure, Turner said, by checking everything you bring along to a field research job, such as flares and radio beacons.

And the training helped her in other ways, too. “You can apply these skills for coping with stress anywhere, even in an office job,” said Turner.

Hopefully without any hungry bears bearing down on your cubicle.