Communities dependent on shellfish and marine resources could be at risk

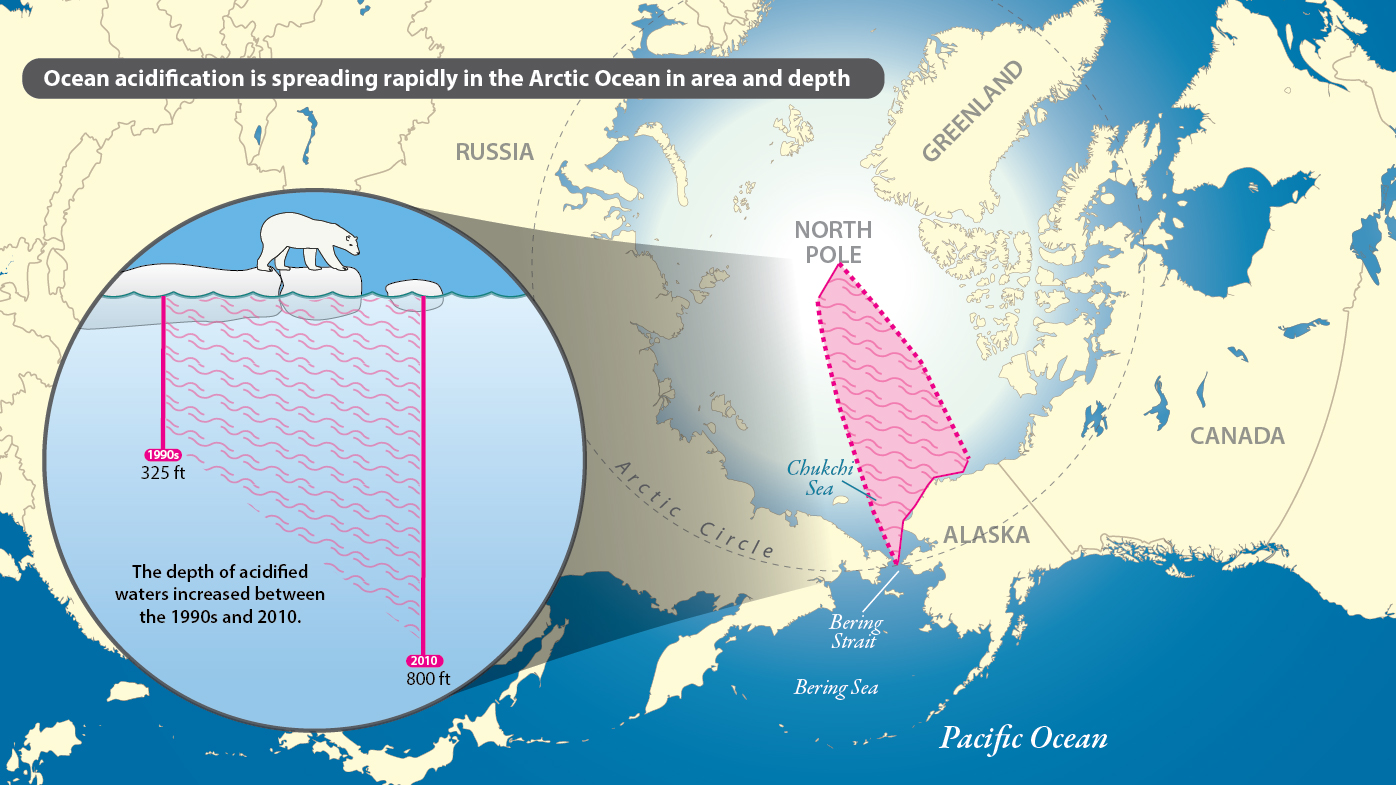

Ocean acidification is spreading rapidly in the western Arctic Ocean in both area and depth, potentially affecting shellfish, other marine species in the food web and communities that depend on these resources, according to new research published in Nature Climate Change by NOAA, Chinese marine scientists and other partners.

University of Delaware researcher Baoshan Chen (pictured left) takes water samples from a melting pond on ice in the northern Arctic Ocean basin with a Chinese collaborator. (Image credit: Courtesy of Di Qi and Zhongyong Gao, Third Institute of Oceanography, State Oceanic Administration of China, Xiamen, China)