Healthy coral reefs are one of Earth’s most valuable ecosystems, and support thousands of marine life species. Here, black sea bass swim through the reef in Gray’s Reef National Marine Sanctuary. (Image credit: NOAA)

Magnuson-Stevens Act: A unique charge for sustainable seafood

Success by the numbers

The science behind bycatch reduction

Using a holistic approach to keeping fisheries sustainable

The best available science, based on the best available technology

Here at NOAA, we’re excited to celebrate the 40th birthday of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act.

Enacted on April 13, 1976, it is the primary law governing fishing in the United States, setting up a system that joins fishermen, NOAA, coastal states and other stakeholders in working together on America’s fisheries.

1.73 million

The number of U.S. jobs supported by commercial and recreational fishing

Through eight regional fishery management councils, each state brings key players to the table — including commercial and recreational fishermen, conservationists and scientists. The United States also has three state fishery management commissions.

Together, we work to keep fish stocks healthy, sustainable and resilient. The numbers show our success: 39 fish stocks have been rebuilt since the year 2000. Successes include rebuilt stocks in every region of the country — golden tilefish in the Mid-Atlantic, canary rockfish along the West Coast, and gag grouper in the Gulf of Mexico.

Our latest Status of the Stocks Report shows 91 percent of stocks with known status are not on the overfished list. Overfishing happens when the harvest rate is too high. And 84 percent of fish stocks with known status are at healthy population levels. NOAA updates the status of stocks each year.

Even when a stock is overfished, the Magnuson-Stevens management system allows a limited harvest to keep fishermen working while the fishery rebuilds. This rewards fishermen for compliance and stewardship, and keeps our economy going while the stock’s population grows. United States federal fisheries operate under the same national standards and robust fishery management plans.

Our science-based management process includes assessing fish stocks, establishing catch limits and reducing bycatch.

Fishery bycatch is a complex issue. Even the word is complicated because it means different things to different people.

When some people talk bycatch, they mean the fish a fisherman doesn’t want to catch — either because they’re going after a different fish or because regulations say they can’t keep that fish. But bycatch, as NOAA defines it, also includes harm that fishing gear may cause to other animals, such as marine mammals, seabirds, corals, sponges, sea turtles and protected fish.

Working under the Magnuson-Stevens Act for the past 40 years, the United States has maintained a firm commitment to reduce bycatch. But like many of the issues facing our changing ocean, bycatch is an issue NOAA cannot address alone. We work with fishermen, management partners, researchers, conservation organizations and others to find solutions to improve life for both the fish and the fishermen. That, in turn, benefits our nation’s economy. Reducing bycatch is a winning proposition all around.

NOAA works with many partners on multiple fronts to develop innovative solutions to minimize bycatch here, and help others do so abroad. For example, one recent report to Congress notes that the simple addition of LED lights on nets in the West Coast ocean shrimp trawl fishery reduced bycatch of a protected fish called eulachon by up to 91 percent. On the other side of the country, real-time maps identifying butterfish hotspots reduced bycatch of the species in the Northeast longfin squid fishery by 54 percent in 2 years.

Although the United States takes pride in the great strides made in reducing the threat bycatch presents to global sustainability and resiliency, there is still more work to do. Recognizing this, NOAA released a draft strategy in February 2016 that further commits NOAA and our partners to monitor and estimate bycatch rates in fisheries, then research and develop solutions.

The strategy provides a coordinated national approach to identifying and addressing challenges at a regional level and underscores NOAA’s commitment to continuing to build resilient, healthy, sustainable marine ecosystems.

Just as doctors keep the wellness of the entire body in mind when addressing an illness, NOAA looks at the ecosystem as a whole when managing a single fishery — something scientists refer to as ecosystem-based management.

Ecosystem-based management means scientists diagnose the health, function and resilience of the broader natural resource to benefit of the organisms that live in it. This is especially important as climate change and ocean acidification continue to alter our marine environment.

Through the Magnuson-Stevens Act, science is evolving to include a broader look at the constantly changing environment within a specific underwater area to inform fisheries policy and decisions.

For example, a recent study identified a set of features common to all ocean ecosystems, providing a visual diagnosis of what’s happening in the ocean. Together, the features detail the cumulative effects of threats — such as overfishing, pollution, and invasive species — so responders can act quickly to increase resilience and sustainability. This is a giant leap forward in our science.

Scientists incorporate satellite imagery, fishery surveys and landings data, among other things, to produce a visual image of the patterns in the ecosystem food chain. These patterns show if and when there is a problem. Scientists can also use data in reverse to see how an ecosystem is recovering after a threat is reduced, such as how an ecosystem is recovering after an oil spill.

As a world leader in sustainable fishery management, NOAA and our partners are always looking for ways to improve. Doing this means staying on the cutting edge of innovation, using the authority provided through the Magnuson-Stevens Act.

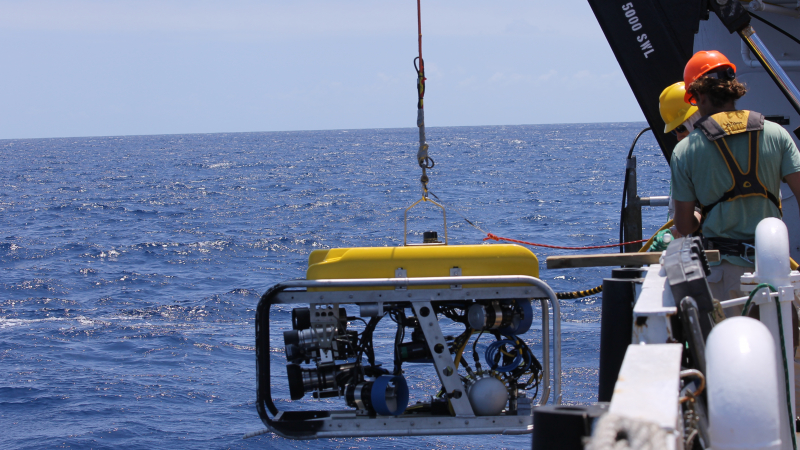

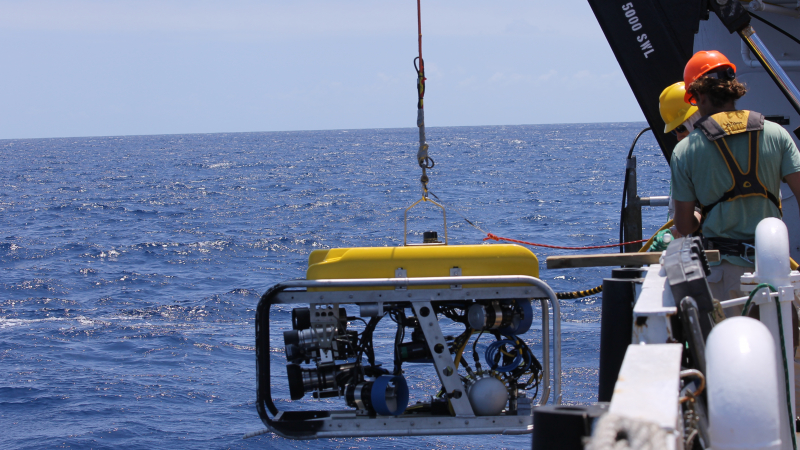

One wave of the future is technology that will look at the DNA in a water sample to identify animals living in that area. But while that’s still in the works, there is already plenty of cool factor in the field. Unmanned vehicles — both above the waves and beneath the surface — provide a couple of great examples.

More and more unmanned aircraft are taking flight to give scientists a new way to study marine life without getting too close. Research is also evolving beneath the waves. Case in point — the Gulf of Maine. There, scientists put microphones on underwater robots and sent them out to listen for a noise that spawning cod make. With New England cod stocks in bad shape, the recordings help researchers locate and protect places important to the species.

New technology is also helping scientists estimate fish stocks — a critical part of sustainable fish management. And seeing is believing! NOAA Fisheries is putting underwater cameras on fish traps to find, count and measure fish in the Southeast.

Another good example includes sonar on the seafloor in the Gulf of Alaska, an important spawning area for walleye pollock — one of the most valuable fisheries in the nation. This sonar helps scientists monitor fish in the water column above it to improve fish surveys.

Here at NOAA, we’re excited to celebrate the 40th birthday of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act.

Enacted on April 13, 1976, it is the primary law governing fishing in the United States, setting up a system that joins fishermen, NOAA, coastal states and other stakeholders in working together on America’s fisheries.

1.73 million

The number of U.S. jobs supported by commercial and recreational fishing

Through eight regional fishery management councils, each state brings key players to the table — including commercial and recreational fishermen, conservationists and scientists. The United States also has three state fishery management commissions.

Together, we work to keep fish stocks healthy, sustainable and resilient. The numbers show our success: 39 fish stocks have been rebuilt since the year 2000. Successes include rebuilt stocks in every region of the country — golden tilefish in the Mid-Atlantic, canary rockfish along the West Coast, and gag grouper in the Gulf of Mexico.

Our latest Status of the Stocks Report shows 91 percent of stocks with known status are not on the overfished list. Overfishing happens when the harvest rate is too high. And 84 percent of fish stocks with known status are at healthy population levels. NOAA updates the status of stocks each year.

Even when a stock is overfished, the Magnuson-Stevens management system allows a limited harvest to keep fishermen working while the fishery rebuilds. This rewards fishermen for compliance and stewardship, and keeps our economy going while the stock’s population grows. United States federal fisheries operate under the same national standards and robust fishery management plans.

Our science-based management process includes assessing fish stocks, establishing catch limits and reducing bycatch.

Fishery bycatch is a complex issue. Even the word is complicated because it means different things to different people.

When some people talk bycatch, they mean the fish a fisherman doesn’t want to catch — either because they’re going after a different fish or because regulations say they can’t keep that fish. But bycatch, as NOAA defines it, also includes harm that fishing gear may cause to other animals, such as marine mammals, seabirds, corals, sponges, sea turtles and protected fish.

Working under the Magnuson-Stevens Act for the past 40 years, the United States has maintained a firm commitment to reduce bycatch. But like many of the issues facing our changing ocean, bycatch is an issue NOAA cannot address alone. We work with fishermen, management partners, researchers, conservation organizations and others to find solutions to improve life for both the fish and the fishermen. That, in turn, benefits our nation’s economy. Reducing bycatch is a winning proposition all around.

NOAA works with many partners on multiple fronts to develop innovative solutions to minimize bycatch here, and help others do so abroad. For example, one recent report to Congress notes that the simple addition of LED lights on nets in the West Coast ocean shrimp trawl fishery reduced bycatch of a protected fish called eulachon by up to 91 percent. On the other side of the country, real-time maps identifying butterfish hotspots reduced bycatch of the species in the Northeast longfin squid fishery by 54 percent in 2 years.

Although the United States takes pride in the great strides made in reducing the threat bycatch presents to global sustainability and resiliency, there is still more work to do. Recognizing this, NOAA released a draft strategy in February 2016 that further commits NOAA and our partners to monitor and estimate bycatch rates in fisheries, then research and develop solutions.

The strategy provides a coordinated national approach to identifying and addressing challenges at a regional level and underscores NOAA’s commitment to continuing to build resilient, healthy, sustainable marine ecosystems.

Just as doctors keep the wellness of the entire body in mind when addressing an illness, NOAA looks at the ecosystem as a whole when managing a single fishery — something scientists refer to as ecosystem-based management.

Ecosystem-based management means scientists diagnose the health, function and resilience of the broader natural resource to benefit of the organisms that live in it. This is especially important as climate change and ocean acidification continue to alter our marine environment.

Through the Magnuson-Stevens Act, science is evolving to include a broader look at the constantly changing environment within a specific underwater area to inform fisheries policy and decisions.

For example, a recent study identified a set of features common to all ocean ecosystems, providing a visual diagnosis of what’s happening in the ocean. Together, the features detail the cumulative effects of threats — such as overfishing, pollution, and invasive species — so responders can act quickly to increase resilience and sustainability. This is a giant leap forward in our science.

Scientists incorporate satellite imagery, fishery surveys and landings data, among other things, to produce a visual image of the patterns in the ecosystem food chain. These patterns show if and when there is a problem. Scientists can also use data in reverse to see how an ecosystem is recovering after a threat is reduced, such as how an ecosystem is recovering after an oil spill.

As a world leader in sustainable fishery management, NOAA and our partners are always looking for ways to improve. Doing this means staying on the cutting edge of innovation, using the authority provided through the Magnuson-Stevens Act.

One wave of the future is technology that will look at the DNA in a water sample to identify animals living in that area. But while that’s still in the works, there is already plenty of cool factor in the field. Unmanned vehicles — both above the waves and beneath the surface — provide a couple of great examples.

More and more unmanned aircraft are taking flight to give scientists a new way to study marine life without getting too close. Research is also evolving beneath the waves. Case in point — the Gulf of Maine. There, scientists put microphones on underwater robots and sent them out to listen for a noise that spawning cod make. With New England cod stocks in bad shape, the recordings help researchers locate and protect places important to the species.

New technology is also helping scientists estimate fish stocks — a critical part of sustainable fish management. And seeing is believing! NOAA Fisheries is putting underwater cameras on fish traps to find, count and measure fish in the Southeast.

Another good example includes sonar on the seafloor in the Gulf of Alaska, an important spawning area for walleye pollock — one of the most valuable fisheries in the nation. This sonar helps scientists monitor fish in the water column above it to improve fish surveys.